The CEO of one company that I work with lamented that his leadership team was discussing a reorganization again. And that although he was not again reorganizing in itself, the last reorganization had not really solved any of the issues the company struggled with. Consequently, he was concerned that this new reorg would throw up a lot of dust, but again not solve any of the core issues.

The CEO of one company that I work with lamented that his leadership team was discussing a reorganization again. And that although he was not again reorganizing in itself, the last reorganization had not really solved any of the issues the company struggled with. Consequently, he was concerned that this new reorg would throw up a lot of dust, but again not solve any of the core issues.

Reflecting on his words, I realized that this is my experience in every reorganization that I have been involved in, either as an employee or as a consultant. The process is obvious for anyone who has been part of leadership teams: someone brings up a problem and then builds the case that the problem is not unique, but actually the symptom of a systemic root cause. The next step is to show that not addressing this systemic problem will cause the company to go to hell in a handbasket. Subsequently, the protagonist shows that this systemic problem is due to the organizational structure and alignment of roles and responsibilities and that organizing differently will solve all the concerns, has many additional benefits and will solve world hunger, global warming, etc. After some debate, the others in the team feel that being against the reorg will make them stand out like a stuck-in-the-mud traditionalist, which would be bad for their careers, and start to sing the praises of the reorg as well. The end result is that the reorg is approved, everyone in the management teams tells publicly how important it is to get this done quickly and that they need the support from everyone in the organization and the change is initiated.

What happens in practice? In reality, dozens, hundreds or sometimes thousands of people’s professional lives are affected. Ongoing priorities get disrupted. The organization falls into a period of paralysis as it’s unclear who actually is responsible for things. People leave as they don’t want to be part of a dysfunctional organization. Etcetera. After some time, the organization recovers, often largely due to the informal organization and people taking responsibility despite, rather than thanks to, the formal organization and the output recovers. Management takes this as a sign of success, beats themselves on the chest and congratulate themselves on having saved the company from certain doom. Then, after some quarters or at most a few years, the same problems that were present before the last reorg start to reappear again and the whole process repeats itself. Like the movie Groundhog Day.

So, it is time to stop this madness. Reorganizations, in and of themselves, do not solve anything and are harmful. Not a little, but very harmful. In too many organizations, they are used to show activity and decisiveness of key individuals that seek to protect or improve their position on the back of company. Although this is a bit of an oversimplification, there are at least three problems that I see occurring in practice: the pendulum problem, the culture problem and the inconsistent business strategy problem.

The pendulum problem is the situation where the company swings back and forth between two extremes in terms of organizational structure. This can be between centralization and decentralization, between separating and combining business and R&D, between being platform centric or being customer or product centric, etc. The core of the problem is that each extreme has a set of benefits and a set of disadvantages. The company is unable to accept the advantages and to put mechanisms in place to deal with the disadvantages of the organizational setup. Hence it swings back and forth.

The culture problem is where the culture in the company is stronger than the official strategy and structure. A typical example is the hero worship culture. Here, the official strategy of the company is to ensure quality and reliability through processes, consistent ways of working and other mechanisms. However, whenever there is an issue with customers in the field, a product that is late or some other unplanned situation, the hero culture takes over and a key individual or core team gets completely free reigns to solve the issue at hand. And, of course, the team gets applauded when they to wrestle the issue to the ground. Rather than addressing the key issue at an architectural, process and organizational level to ensure that these problems can’t occur, the organization relies on heros to pull them out of the fire. For those working in the automotive industry, the notion of “task forces” represent an illustrative example of this pattern.

The third type of problem is concerned with inconsistent business strategies. This problem occurs when the organization sets a business strategy that is inherently conflicting. For instance, some companies desire to be deeply customer centric and achieve high levels of reuse in the solutions they offer. Although this looks great at the powerpoint level, the fact is that you can’t combine these strategies and expect to deliver on both. High levels of reuse require standardization and productification of functionality. Deep customer intimacy requires significant amounts of customization and customer specific development. Trying to solve this contradictory situation causes the organization to focus on platforms on the one hand and customer teams on the other hand without clear guidance on who leads and who follows. It then results into a highly politicized organization where the personalities of individuals determine the balance achieved in practice. Companies tend to then go through a series of reorganizations to resolve this inherent conflict without realizing that the problem can not be solved at the organizational level.

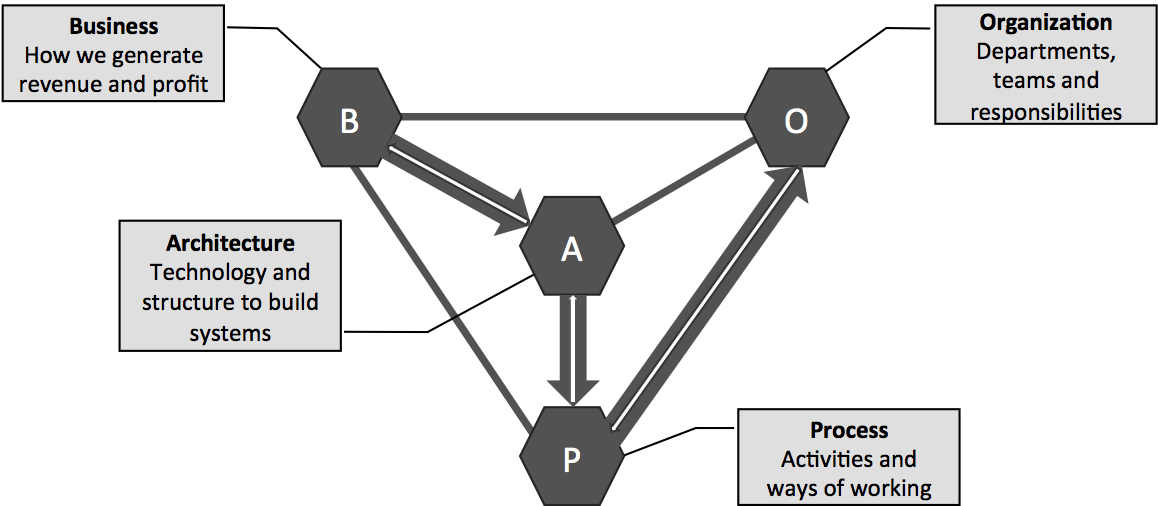

Although there are several additional symptoms and problems that I could have brought up, I would like to spend some attention on resolving these issues. The first tool that I have found incredibly useful (undoubtedly as I was part of developing it in the first place) is the BAPO model. As shown in the figure below, the BAPO model suggests that the best approach to design an organization is to follow four steps:

- Business and business strategy: Clearly define the business and business strategy that you’re in and want to be in. Be explicit about what you define as the strategy to make you successful in the future.

- Architecture and technology choices: Based on the understanding of the business strategy, define the desired architecture for the products, solutions and services that you are offering as well as the technology choices that allow you to optimally deliver on the business strategy.

- Process, ways of working and tools: The next step is to design the processes that the company should use to deliver. This also includes the ways of working and the tooling that helps the company automate the repetitive and standardized tasks.

- Organization: Based on the above and ONLY after having defined the first three elements should one even being to think about organization. And rather than going deep on management and reporting hierarchies, the focus should be on empowerment, autonomy of teams and quantitative goals that directly align teams with business success in terms of revenue and margins.

Figure: The BAPO model

The second topic that deserves mentioning is culture. As the saying goes, culture eats strategy for breakfast (and lunch and dinner). Companies with a strong culture are fabulous to work in as long as the culture aligns with the reality of the business ecosystem. The strong culture requires very few formal governance mechanisms as people automatically do the right thing as the culture dictates what the right behaviors are. So, everyone in the organization feels empowered and free to do the right thing as many do not even realize that the culture is what is causing them to behave this way.

The moment the culture turns orthogonal to, or at least less than optimal for the business reality, the strong culture becomes a liability. In fact, the strong culture can become the very thing that sinks a company. Driving cultural change is notoriously hard, but part of the keys is to drive for self-reflection in the culture. This means that everyone frequently reflects on why the organization behaves in certain ways and whether this still is the right approach in the current situation. A self-reflective culture allows the culture to evolve in accordance with the changes in the business context in which the company operates. In fact, empowered organization without managers and high levels of autonomy for individuals and teams use self-reflection as a mechanism to drive evolution and continued relevance in the marketplace.

Concluding, the vast majority of reorganizations are absolute and utter waste that serve the needs of a few at the expense of the many. We should stop this idiocy and be highly skeptical of any proposal for reorganization. Instead, getting crystal clear on the BAPO for your company and aligning the organization around that is critical for prolonged business success. In addition, ensuring a company culture that is self-reflective and that continuously evaluates itself for alignment with the business reality in the ecosystem is critical. In most cases, a reorg is the easy way out that allows leaders to avoid the real, hard work that is required to keep the company competitive. Don’t fall into that trap and focus on what really matters!

Follow me on janbosch.com/blog, LinkedIn (linkedin.com/in/janbosch) or Twitter (@JanBosch)!